Be Cautious About Raising The Corporation Tax Rate

The Chancellor has been reported as considering a rise in the corporation tax rate in next week’s budget. At a time of a massive public sector deficit, it is certainly a responsibility of his to consider how extra revenue could be generated. And politically this is a tax increase that Labour finds difficult to oppose.

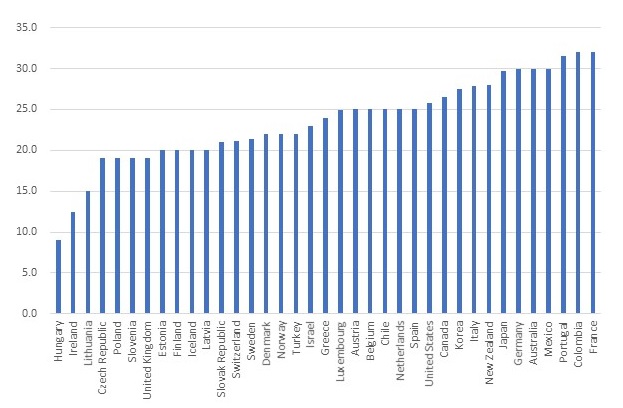

The case may seem even more compelling when comparing the current UK corporation tax rate of 19% to the rates in other OECD countries, shown in Figure 1. Only Hungary, Ireland and Lithuania have lower rates than the UK, taking into account both central and sub-central taxes.

Figure 1. Corporation Tax Rates in the OECD, 2020

Source: OECD Corporate Tax Statistics Database

Nevertheless, the Chancellor should be very cautious. Here are five reasons why.

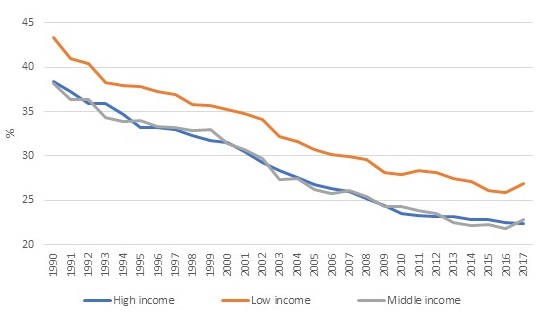

First, raising tax rates on profit would go in the opposite direction to the trends over the last 35 years, driven by competition amongst countries to attract inward investment. The UK has been an aggressive contributor to this process of international competition, which on average has driven down rates by roughly one percentage point a year. This is illustrated in Figure 2, and applies to tax rates in high, middle and low income countries.

That competition has not disappeared. Instead it has intensified with the 2017 US tax reform - that was a further decisive play in the tax competition game, reducing the US rate from 35% to 21%, and pushing down the average still further. Before 2017 other countries could perhaps justify higher rates by reference to the US – but no longer, even if the new US administration would like to raise the US rate.

Figure 2. Average Corporation Tax Rates in High, Middle and Low Income Countries, 1990-2017

Source: IMF FAD Rates Database

Second, the tax rate does not tell the whole story about the generosity of the UK corporation tax. What also matters is the definition of the profit in the tax base – including the generosity of capital allowances, and the strength of anti-avoidance rules, for example. The Centre for Business Taxation has pioneered international comparisons of effective tax rates, taking into account both the tax rate and tax base. These show a rather different picture for the UK.

According to recent calculations by the OECD for 2019, 24 OECD countries (out of 36 analysed) had a lower effective marginal tax rate than the UK. The reason is that while the UK has focused on reducing its statutory rate, it has offset this over the years by broadening its tax base beyond that in most other countries. The competitive advantage of the UK is certainly not well measured by statutory rate alone. To reduce the negative impact on the effective tax rate of a rise in the statutory tax rate, the Chancellor would have to narrow the tax base.

Third, effective tax rates matter for investment. There has been a wealth of academic research on the question of how differences in effective tax rates affect flows of foreign direct investment – and the evidence suggests a sizable impact. A consensus estimate is that inward foreign direct investment falls by 2.5% for every one percentage point increase in the corporation tax rate. Roughly, then a 4 percentage point rise in the tax rate would reduce inward investment by 10%. That would be unwelcome, to say the least, at a time of a very significant downturn in the economy.

Fourth, the UK economy is being hit hard not only by the covid-19 pandemic, but by Brexit. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many businesses are moving out of the UK due to the higher costs of trading with the EU. This is then a doubly bad time to raise the corporation tax rate under the current system.

Fifth, it is perhaps understandable that, in a time when revenue needs are great, public opinion would support a rise in taxes on business – that seems to keep the burden away from income tax, or VAT, falling on ordinary people. But this is a false comparison. Taxes on business must ultimately fall on people as well – shareholders, consumers, employees and suppliers; with taxes on business it is just more difficult to figure out which people are more affected. Despite a long academic literature analysing who is worse off due to taxes on profit, there is still a dearth of evidence as to how progressive – or regressive – the corporation tax is, in terms of being ultimately borne more by individuals with higher or lower income.

There is a better way.

The economic problems arising from raising the corporation tax rate stem from the fact that it is levied, broadly, where production and other economic activity takes place. I have argued – most recently in a book with several co-authors [1] – that it is possible to avoid this problem by moving where we tax profit to the country where sales are made. Raising tax rates on profit in the country of the market would not have the economic disadvantages set out here, since a country with a higher tax rate would not deter businesses from locating productive economic activity there. That is a long-run strategy that would enable the Chancellor to increase revenue from taxing profits without the consequential negative effects on the economy.

Relevant research from the Centre for Business Taxation:

- Taxing Profit in a Global Economy, Michael P. Devereux, Alan J. Auerbach, Michael Keen, Paul Oosterhuis, Wolfgang Schön and John Vella, Oxford University Press, 2021

- CBT Corporate Tax Ranking, Katarzyna Bilicka and Michael P. Devereux

[1] Taxing Profit in a Global Economy, Michael P. Devereux, Alan J. Auerbach, Michael Keen, Paul Oosterhuis, Wolfgang Schön and John Vella, Oxford University Press, 2021