Are investment incentives effective in uncertain times?

We live in uncertain times. And in uncertain times, the private sector needs a different fiscal policy mix than the one that is optimal in normal times. For a government that wants to stimulate investment by the private sector, we find in recent research that tax policy stimulus will be less effective if a large fraction of companies is exposed to elevated uncertainty.

For governments around the world, a popular supply-side stimulus policy is changing the tax treatment of capital expenditures. Take the case of a company that purchases a machine worth $50,000, for example. In most corporate tax systems, and without an accelerated depreciation policy, the company cannot immediately deduct the full cost of this machine from its taxable income in the year of purchase. If the machine is subject to straight-line depreciation over 10 years, for instance, the company can normally only deduct $5,000 each year for 10 years from its taxable income. The net present value of these deductions to a firm that pays tax at 20% corporate tax rate and discounts future cash flows at a 10% rate is $6,760. An accelerated depreciation policy that allows full expensing would provide the firm with an extra cash amount of $10,000, calculated as the tax benefit of being able to deduct the full cost of the machinery in the year of purchase ($50,000 x 20%). The net benefit to the firm in this case is $10,000-$6,760 = $3,240. For firms that use machinery with long useful lives, or for firms that discount future cash flows at higher rates (e.g. smaller companies), the cash flow benefits of such measures can be much higher.

Some accelerated depreciation or super-deduction measures are implemented in good times, and some are implemented with the aim of putting the private sector back on its feet in bad times. Recent examples include the UK government’s introduction of a super-deduction for investment1 in its 2021 Budget, the US government’s Bonus Depreciation policies during the 2000s as well as the full expensing of capital spending under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, and Germany’s accelerated depreciation policy as part of its Kraftpaket 2020.

In our paper forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Economics, we explore the effectiveness of tax breaks for investment under two different economic scenarios. The first reform that we evaluate was implemented at a time of stability, and companies responded strongly with a positive investment response. The second reform, on the other hand, was implemented in a period of high uncertainty, and did not prove very effective in stimulating investment across the board. However, the impact of stimulus policy in the high uncertainty scenario was nuanced: companies that were sheltered from elevated uncertainty still responded strongly to the policy, and the firms that were exposed to high uncertainty drove the drop in the overall response.

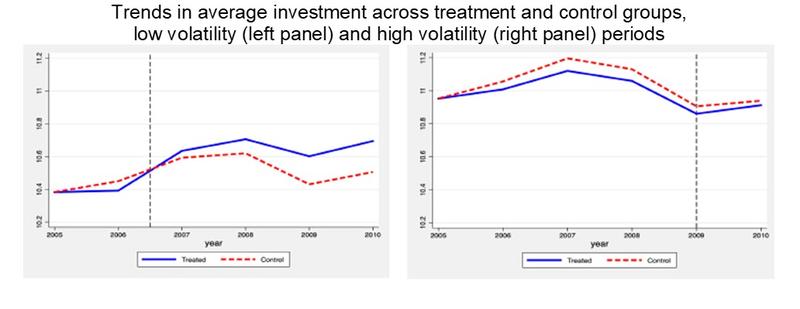

To establish this result, we made use of two reforms implemented in Poland, two years apart. In each reform, companies below a size threshold became eligible to the more generous policy and companies above the size threshold did not. In the graph, we label the eligible firms as ‘Treated’, and the firms that have similar characteristics to treated firms, but that were ineligible, as ‘Control’.

In the graph above, we assess the trajectories of average investment for treated firms relative to control firms for the low volatility period in the left panel, and for the high volatility period in the right panel.2 While treated firms substantially increased investment relative to control firms in the low volatility period, we do not see a material relative increase in the right-hand panel, which captures the responses (or the lack of a response) in the high volatility period.

This finding is important to highlight the limitations of supply side fiscal stimulus, or tax breaks for companies in periods of elevated uncertainty. We find that companies are less likely to invest, even in the presence of generous capital allowances, if they are faced with high uncertainty.

In the paper, the recession period that we examine is the global financial crisis of 2008-09. Of course, it is no surprise that periods of elevated uncertainty are also periods with large company losses. Thanks to our detailed dataset, in the paper, we rule out alternative explanations for why investment did not respond to the tax stimulus. Such alternative explanations include the lack of response due to loss-making, thereby rendering a ‘tax benefit’ meaningless, or changes in terms of trade, leaving exporting or importing firms at a disadvantage depending on the effects of recession on exchange rates.

These findings show that elevated uncertainty contributes to the lower multipliers for tax policy during recessions, limiting the impact of supply-side stimulus measures such as investment tax incentives during downturns. In such periods, demand-side instruments may be more effective in generating output, at least in the short run.

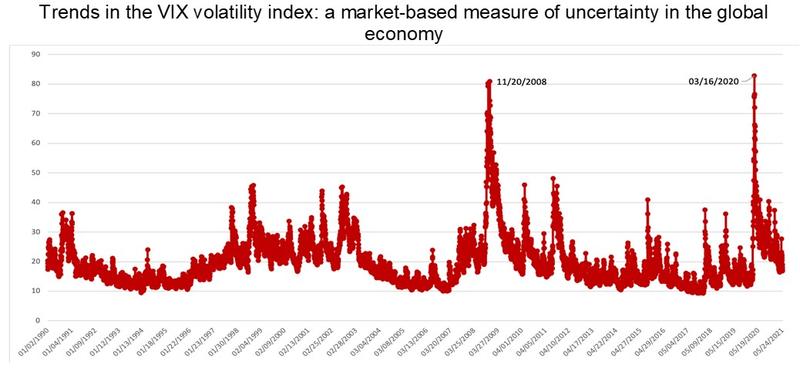

The second graph in this blog shows the trajectory of the CBOE’s VIX volatility index that captures the market’s perception of economic uncertainty. The 2020 peak in this index is strikingly similar to the 2008 peak, which is the period that we have examined in this paper. Despite uncertainty having dampened since March 16, 2020, the current levels are still higher than those of mid-1990s and mid-2000s. Now, for each country, aggregate investment movement in response to stimulus is going to depend on the distribution of firms in their exposure to elevated uncertainty.

1 CBT Blog titled “What will the Budget do for Corporate Investment?” by Michael Devereux dated 5 March 2021 examines the possible effects of this policy.

2 The investment variables are in natural logarithm in the two graphs. Both categories’ average investment levels are normalised to the 2005 group average for comparability.

Relevant CBT work:

Guceri, I.; Albinowski, M. (forthcoming). “Investment Responses to Tax Policy under Uncertainty”, Journal of Financial Economics (earlier version previously circulated as part of the Centre for Business Taxation Working Paper series WP20/07).

“What will the Budget do for Corporate Investment?” by Michael Devereux dated 5 March 2021