Cleaning Up the U.S. Tax System?

The House and the Senate have passed tax reform bills in the U.S. The process has reminded me of how my 8-year-old son washes the dinner dishes: fast and without attention to detail. If you’ve ever had an 8-year-old, (or been an 8-year-old) you know what I mean.

The bills are designed to fix America’s “broken” tax code, which has been robustly criticized by both political parties over the past decade. Exactly what the bills are designed to “fix” is not entirely clear, but popular choices include: 1) bringing the statutory corporate tax rate into line with other industrialized nations; 2) reducing incentives to stash corporate earnings abroad; and 3) reducing incentives to avoid corporate tax payments. To achieve these objectives, both bills contain provisions designed to reduce corporate taxes and increase personal taxes. The reform, however, will at best be a partial solution to the myriad problems in America’s tax system, and will undoubtedly create some unintended effects.

I therefore ask myself (and you probably do too) is Congress doing a better job reforming the tax code than my 8-year-old does washing dishes?

Let’s tackle just one issue: shifting corporate income to low-tax countries (aka tax havens) to avoid taxes. Under current U.S. corporate tax rules, U.S. companies have an incentive to strategically shift income out of the U.S. to tax havens. There are two key factors that drive this incentive: the after-tax rate of return on investments in the U.S. compared to after-tax rate of return on investments in the tax haven, and the expected repatriation tax rate in the year of repatriation. To keep the analysis here simple, I’ll hold after-tax rates of return constant at 6.5%, and focus on the effect of repatriation taxes.

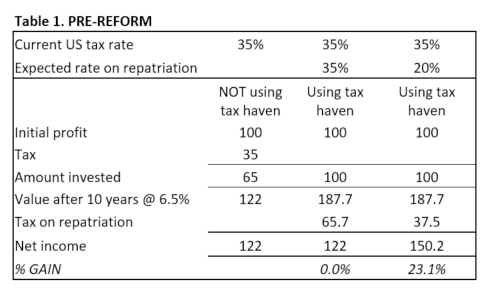

Table 1 below shows the position before the reform for companies that earn $100 of profit in the U.S. and retain it for 10 years, earning a rate of 6.5%. The first column shows that $100 earned and reinvested in the U.S. for 10 years would be worth $122 after all taxes have been paid. The second column shows that $1 earned and reinvested in a tax haven for 10 years, then repatriated under the current U.S. tax system would also be worth $122. There is no difference – because of the tax on repatriation to the U.S. after 10 years. But if companies expect that the repatriation tax rate will be lower in the future, say 20% instead of 35%, then the value of $1 shifted to a tax haven rises to $150, as shown in the third column. The lower are expected repatriation taxes, the stronger are incentives to shift earnings out of the U.S to a tax haven, and leave them “trapped” while they wait (and lobby) for a tax reduction.

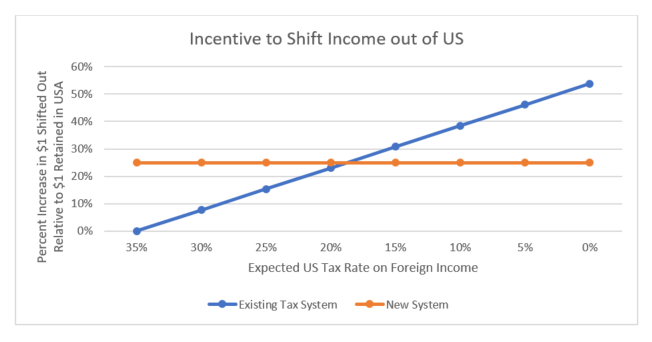

The blue line in the figure below shows how much more $1 of earnings shifted to a tax haven is worth relative to $1 of earnings in the U.S. for various repatriation tax rates. As can be seen, when the repatriation tax rate is 35%, the difference is 0%. But as the repatriation tax rate moves lower and lower, the percentage difference becomes higher and higher, to more than 50%. That’s a big difference! No wonder over $2 trillion is trapped offshore!

Will the tax reform make a difference? Let’s repeat the analysis and focus on two major aspects of the tax reform bills. First, both bills reduce the corporate tax rate to 20%. Second, both bills eliminate repatriation taxes.

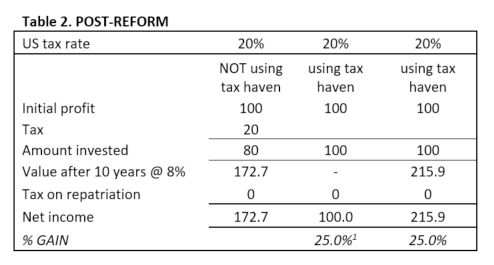

Because the U.S. corporate tax rate will be lower in the new tax system, the after-tax rate of return in the U.S. should be higher - say at 8%. In Table 2 below, the first column shows that $100 earned and reinvested in the U.S. for 10 years is worth $173 after all taxes have been paid. The second column examines what happens if the $100 is shifted to a tax haven. In that case, it could be repatriated immediately without a tax charge. Without any reinvestment, the company could have $100, a gain of 25% over the initial post-tax income of $80 in the U.S. With reinvestment in the U.S. for 10 years, it would be worth $216, still a gain of 25%. This is illustrated by the orange line in the figure above.

Alas, our first inspection of the dinner dishes suggests they are not entirely clean. Simply put, $100 shifted to a tax haven is worth more than $100 earned in the U.S. under the new tax bills. Recognizing this, both the House and the Senate have included so-called base erosion prevention mechanisms designed to curb income shifting behavior. Experience shows, however, that firms are exceptionally clever when navigating complex rules if incentives are strong enough!

To push this further, consider that much of the $2 trillion in “trapped” earnings originated as earnings in high-tax jurisdictions like the U.K. or Germany that were shifted into tax havens. Will the new tax system reduce the incentives of U.S. companies to shift their earnings from high-tax foreign countries into tax havens?

Using a similar approach, it is easy to show that the incentives for U.S. companies to shift earnings from high-tax foreign countries to tax havens will increase under the new regime. Why? In the new tax system, $100 shifted to a tax haven will never face tax anywhere in the world, even if repatriated to the U.S., while $100 shifted to a tax haven in the existing tax system always faces future tax in the U.S. when it is ultimately returned to the U.S.

Holding the dishes up to the light is making them look even worse!

Did my 8-year-old actually do anything? Does this tax reform actually fix anything about America’s “broken” system?

Undoubtedly, the tax reform will solve one pesky problem. Earnings will no longer be “trapped” while corporations wait for lower repatriation taxes, and so the incentive to “invert”, which was largely used as a do-it-yourself eradication of repatriation taxes, will be eliminated. Moreover, a lower corporate tax rate will reduce the cost of capital for U.S. businesses, probably leading to new investment, and increasing economic growth.

Luckily, it appears that the dishes did at least make an entry into a basin of soapy water, and the sponge might have done a little work toward cleaning up the mess. But just how much of last night’s dinner we are willing to tolerate on tomorrow’s breakfast plate is a question we should all be asking.

Scott Dyreng is Associate Professor of Accounting at the Fuqua School of Business, Duke University in North Carolina. Scott is visiting the Centre for Business Taxation between August and December 2017.

[1] Relative to the 80 in column 1 where there is not yet any investment.